Sha Is Perhaps the Most Widely Used Family of Hash Functions.

| Secure Hash Algorithms | |

|---|---|

| Concepts | |

| hash functions· SHA· DSA | |

| Main standards | |

| SHA-0· SHA-1· SHA-2· SHA-iii | |

| Full general | |

|---|---|

| Designers | National Security Agency |

| First published | 1993 (SHA-0), 1995 (SHA-1) |

| Series | (SHA-0), SHA-1, SHA-2, SHA-3 |

| Certification | FIPS PUB 180-4, CRYPTREC (Monitored) |

| Cipher detail | |

| Digest sizes | 160 bits |

| Cake sizes | 512 bits |

| Construction | Merkle–Damgård construction |

| Rounds | eighty |

| Best public cryptanalysis | |

| A 2011 assault past Marc Stevens tin can produce hash collisions with a complication between ii60.three and 265.3 operations.[1] The first public collision was published on 23 Feb 2017.[two] SHA-1 is prone to length extension attacks. | |

In cryptography, SHA-1 (Secure Hash Algorithm ane) is a cryptographically broken[three] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] simply nevertheless widely used hash part which takes an input and produces a 160-bit (20-byte) hash value known as a message digest – typically rendered every bit a hexadecimal number, twoscore digits long. It was designed by the United states of america National Security Agency, and is a U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard.[10]

Since 2005, SHA-ane has non been considered secure against well-funded opponents;[11] equally of 2010 many organizations have recommended its replacement.[12] [9] [xiii] NIST formally deprecated use of SHA-one in 2011 and disallowed its use for digital signatures in 2013. As of 2020[update], called-prefix attacks against SHA-1 are applied.[5] [vii] As such, it is recommended to remove SHA-one from products as soon equally possible and instead utilise SHA-2 or SHA-3. Replacing SHA-1 is urgent where it is used for digital signatures.

All major web browser vendors ceased credence of SHA-1 SSL certificates in 2017.[14] [8] [three] In February 2017, CWI Amsterdam and Google announced they had performed a standoff set on against SHA-1, publishing two dissimilar PDF files which produced the aforementioned SHA-one hash.[15] [2] Nevertheless, SHA-one is however secure for HMAC.[16]

Microsoft has discontinued SHA-one code signing support for Windows Update on August 7, 2020.

Development [edit]

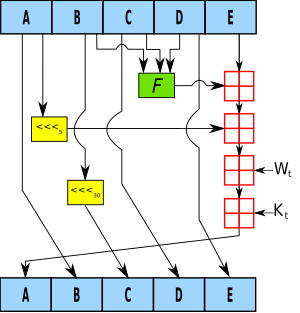

One iteration inside the SHA-1 compression function:

A, B, C, D and E are 32-bit words of the state;

F is a nonlinear part that varies;

denotes a left fleck rotation by northward places;

due north varies for each performance;

Westt is the expanded message give-and-take of round t;

Kt is the round abiding of circular t;

![]() denotes addition modulo ii32.

denotes addition modulo ii32.

SHA-1 produces a message digest based on principles similar to those used past Ronald L. Rivest of MIT in the design of the MD2, MD4 and MD5 message digest algorithms, but generates a larger hash value (160 bits vs. 128 bits).

SHA-1 was developed every bit part of the U.S. Government'southward Capstone project.[17] The original specification of the algorithm was published in 1993 under the championship Secure Hash Standard, FIPS PUB 180, by U.S. authorities standards bureau NIST (National Establish of Standards and Technology).[18] [xix] This version is now ofttimes named SHA-0. It was withdrawn past the NSA shortly after publication and was superseded by the revised version, published in 1995 in FIPS PUB 180-i and commonly designated SHA-1. SHA-1 differs from SHA-0 only by a single bitwise rotation in the bulletin schedule of its compression role. According to the NSA, this was done to right a flaw in the original algorithm which reduced its cryptographic security, but they did not provide any further caption.[twenty] [21] Publicly bachelor techniques did indeed demonstrate a compromise of SHA-0, in 2004, before SHA-1 in 2017. Meet #Attacks

Applications [edit]

Cryptography [edit]

SHA-1 forms role of several widely used security applications and protocols, including TLS and SSL, PGP, SSH, S/MIME, and IPsec. Those applications tin can too apply MD5; both MD5 and SHA-i are descended from MD4.

SHA-i and SHA-2 are the hash algorithms required by police for use in sure U.S. government applications, including use within other cryptographic algorithms and protocols, for the protection of sensitive unclassified information. FIPS PUB 180-i also encouraged adoption and utilise of SHA-one past private and commercial organizations. SHA-1 is being retired from near authorities uses; the U.S. National Establish of Standards and Technology said, "Federal agencies should cease using SHA-1 for...applications that crave standoff resistance as soon as applied, and must use the SHA-2 family of hash functions for these applications after 2010" (emphasis in original),[22] though that was after relaxed to allow SHA-1 to be used for verifying old digital signatures and time stamps.[23]

A prime motivation for the publication of the Secure Hash Algorithm was the Digital Signature Standard, in which information technology is incorporated.

The SHA hash functions take been used for the footing of the SHACAL block ciphers.

Data integrity [edit]

Revision control systems such as Git, Mercurial, and Monotone apply SHA-1, not for security, merely to identify revisions and to ensure that the data has not changed due to accidental abuse. Linus Torvalds said about Git:

- If you have disk corruption, if y'all have DRAM corruption, if you have any kind of problems at all, Git volition observe them. Information technology's not a question of if, it's a guarantee. You can have people who try to exist malicious. They won't succeed. ... Nobody has been able to break SHA-one, but the point is the SHA-1, every bit far as Git is concerned, isn't even a security characteristic. Information technology'southward purely a consistency check. The security parts are elsewhere, then a lot of people assume that since Git uses SHA-1 and SHA-1 is used for cryptographically secure stuff, they call back that, Okay, it's a huge security feature. Information technology has aught at all to do with security, it's just the best hash you can get. ...

- I guarantee you, if you put your data in Git, yous can trust the fact that v years later on, afterward it was converted from your hd to DVD to any new engineering and you copied information technology along, five years later you can verify that the data you get back out is the exact same information y'all put in. ...

- One of the reasons I care is for the kernel, we had a pause in on one of the BitKeeper sites where people tried to decadent the kernel source code repositories.[24] However Git does not require the second preimage resistance of SHA-1 as a security feature, since information technology volition always adopt to keep the earliest version of an object in example of collision, preventing an attacker from surreptitiously overwriting files.[25]

Cryptanalysis and validation [edit]

For a hash function for which L is the number of bits in the message digest, finding a message that corresponds to a given message digest tin ever exist done using a beast force search in approximately 2 L evaluations. This is called a preimage attack and may or may non be practical depending on L and the particular computing environment. However, a collision, consisting of finding two different messages that produce the same message digest, requires on boilerplate only about ane.ii × 2 L/2 evaluations using a birthday set on. Thus the strength of a hash function is usually compared to a symmetric cipher of half the message digest length. SHA-ane, which has a 160-flake message digest, was originally thought to take 80-bit forcefulness.

In 2005, cryptographers Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu produced collision pairs for SHA-0 and have found algorithms that should produce SHA-1 collisions in far fewer than the originally expected 280 evaluations.[26]

Some of the applications that use cryptographic hashes, similar countersign storage, are only minimally affected past a collision set on. Amalgam a password that works for a given business relationship requires a preimage attack, likewise equally access to the hash of the original password, which may or may not be fiddling. Reversing password encryption (e.g. to obtain a countersign to try against a user's business relationship elsewhere) is not made possible past the attacks. (However, even a secure password hash can't foreclose creature-force attacks on weak passwords.)

In the case of document signing, an aggressor could not merely imitation a signature from an existing document: The attacker would have to produce a pair of documents, i innocuous and ane damaging, and get the private cardinal holder to sign the innocuous document. There are practical circumstances in which this is possible; until the stop of 2008, it was possible to create forged SSL certificates using an MD5 collision.[27]

Due to the block and iterative structure of the algorithms and the absence of additional concluding steps, all SHA functions (except SHA-3[28]) are vulnerable to length-extension and fractional-message collision attacks.[29] These attacks allow an attacker to forge a message signed simply by a keyed hash – SHA(message || key) or SHA(primal || message) – by extending the message and recalculating the hash without knowing the central. A simple improvement to prevent these attacks is to hash twice: SHAd(message) = SHA(SHA(0 b || bulletin)) (the length of 0 b , zip block, is equal to the block size of the hash function).

Attacks [edit]

In early 2005, Vincent Rijmen and Elisabeth Oswald published an attack on a reduced version of SHA-one – 53 out of 80 rounds – which finds collisions with a computational effort of fewer than 280 operations.[xxx]

In Feb 2005, an attack past Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu was announced.[4] The attacks tin can discover collisions in the full version of SHA-i, requiring fewer than 269 operations. (A animate being-force search would require 280 operations.)

The authors write: "In particular, our analysis is built upon the original differential assault on SHA-0, the well-nigh standoff assail on SHA-0, the multiblock collision techniques, every bit well as the message modification techniques used in the collision search attack on MD5. Breaking SHA-ane would not be possible without these powerful belittling techniques."[31] The authors have presented a collision for 58-circular SHA-ane, found with two33 hash operations. The paper with the full assault description was published in August 2005 at the CRYPTO briefing.

In an interview, Yin states that, "Roughly, we exploit the post-obit 2 weaknesses: One is that the file preprocessing step is not complicated enough; another is that certain math operations in the commencement twenty rounds take unexpected security problems."[32]

On 17 August 2005, an comeback on the SHA-1 attack was announced on behalf of Xiaoyun Wang, Andrew Yao and Frances Yao at the CRYPTO 2005 Rump Session, lowering the complexity required for finding a collision in SHA-i to 263.[6] On 18 December 2007 the details of this consequence were explained and verified by Martin Cochran.[33]

Christophe De Cannière and Christian Rechberger further improved the set on on SHA-i in "Finding SHA-1 Characteristics: General Results and Applications,"[34] receiving the All-time Paper Award at ASIACRYPT 2006. A two-cake standoff for 64-round SHA-1 was presented, plant using unoptimized methods with 235 compression part evaluations. Since this attack requires the equivalent of about 235 evaluations, it is considered to be a significant theoretical break.[35] Their set on was extended further to 73 rounds (of lxxx) in 2010 by Grechnikov.[36] In society to find an actual standoff in the full eighty rounds of the hash office, however, tremendous amounts of reckoner fourth dimension are required. To that finish, a standoff search for SHA-1 using the distributed computing platform BOINC began August 8, 2007, organized past the Graz University of Applied science. The effort was abandoned May 12, 2009 due to lack of progress.[37]

At the Rump Session of CRYPTO 2006, Christian Rechberger and Christophe De Cannière claimed to have discovered a collision assail on SHA-1 that would allow an assaulter to select at least parts of the bulletin.[38] [39]

In 2008, an assault methodology by Stéphane Manuel reported hash collisions with an estimated theoretical complexity of ii51 to two57 operations.[40] However he later retracted that claim after finding that local collision paths were non really independent, and finally quoting for the nigh efficient a collision vector that was already known before this work.[41]

Cameron McDonald, Philip Hawkes and Josef Pieprzyk presented a hash collision assault with claimed complication ii52 at the Rump Session of Eurocrypt 2009.[42] Withal, the accompanying paper, "Differential Path for SHA-ane with complexity O(252)" has been withdrawn due to the authors' discovery that their estimate was wrong.[43]

I attack against SHA-1 was Marc Stevens[44] with an estimated toll of $ii.77M(2012) to break a single hash value by renting CPU power from cloud servers.[45] Stevens developed this attack in a project called HashClash,[46] implementing a differential path set on. On 8 November 2010, he claimed he had a fully working nearly-collision attack against total SHA-ane working with an estimated complexity equivalent to two57.5 SHA-1 compressions. He estimated this attack could be extended to a full standoff with a complexity around 261.

The SHAppening [edit]

On 8 October 2015, Marc Stevens, Pierre Karpman, and Thomas Peyrin published a freestart standoff attack on SHA-ane'due south compression office that requires only 257 SHA-1 evaluations. This does not straight translate into a collision on the total SHA-1 hash function (where an aggressor is not able to freely choose the initial internal country), but undermines the security claims for SHA-1. In particular, it was the outset time that an attack on full SHA-1 had been demonstrated; all before attacks were as well expensive for their authors to carry them out. The authors named this significant quantum in the cryptanalysis of SHA-i The SHAppening.[9]

The method was based on their earlier piece of work, as well as the auxiliary paths (or boomerangs) speed-upward technique from Joux and Peyrin, and using high performance/cost efficient GPU cards from NVIDIA. The collision was found on a sixteen-node cluster with a total of 64 graphics cards. The authors estimated that a like collision could be establish by buying US$2,000 of GPU time on EC2.[9]

The authors estimated that the toll of renting enough of EC2 CPU/GPU fourth dimension to generate a total collision for SHA-1 at the time of publication was betwixt US$75K and 120K, and noted that was well inside the upkeep of criminal organizations, not to mention national intelligence agencies. As such, the authors recommended that SHA-i exist deprecated as quickly every bit possible.[9]

SHAttered – first public collision [edit]

On 23 February 2017, the CWI (Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica) and Google appear the SHAttered attack, in which they generated two unlike PDF files with the same SHA-one hash in roughly two63.ane SHA-1 evaluations. This attack is about 100,000 times faster than brute forcing a SHA-1 collision with a birthday attack, which was estimated to take 280 SHA-1 evaluations. The assault required "the equivalent processing power of 6,500 years of single-CPU computations and 110 years of unmarried-GPU computations".[2]

Birthday-Well-nigh-Standoff Attack – first practical chosen-prefix attack [edit]

On 24 April 2019 a paper by Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin presented at Eurocrypt 2019 described an enhancement to the previously best chosen-prefix attack in Merkle–Damgård–like assimilate functions based on Davies–Meyer cake ciphers. With these improvements, this method is capable of finding chosen-prefix collisions in approximately 268 SHA-1 evaluations. This is approximately i billion times faster (and now usable for many targeted attacks, thanks to the possibility of choosing a prefix, for example malicious lawmaking or faked identities in signed certificates) than the previous assault'southward ii77.1 evaluations (but without called prefix, which was impractical for most targeted attacks considering the establish collisions were almost random)[47] and is fast enough to be applied for resourceful attackers, requiring approximately $100,000 of deject processing. This method is also capable of finding chosen-prefix collisions in the MD5 function, just at a complexity of two46.3 does not surpass the prior best available method at a theoretical level (239), though potentially at a practical level (≤249).[48] [49] This attack has a retentiveness requirement of 500+ GB.

On v January 2020 the authors published an improved set on.[7] In this paper they demonstrate a chosen-prefix collision set on with a complication of 263.4, that at the time of publication would price 45k USD per generated collision.

SHA-0 [edit]

At CRYPTO 98, two French researchers, Florent Chabaud and Antoine Joux, presented an attack on SHA-0: collisions can be establish with complication two61, fewer than the ii80 for an ideal hash part of the same size.[50]

In 2004, Biham and Chen found near-collisions for SHA-0 – 2 letters that hash to nearly the aforementioned value; in this case, 142 out of the 160 $.25 are equal. They also found total collisions of SHA-0 reduced to 62 out of its eighty rounds.[51]

Afterward, on 12 August 2004, a collision for the full SHA-0 algorithm was appear by Joux, Carribault, Lemuet, and Jalby. This was done by using a generalization of the Chabaud and Joux attack. Finding the collision had complexity 251 and took about 80,000 processor-hours on a supercomputer with 256 Itanium 2 processors (equivalent to 13 days of full-time apply of the computer).

On 17 August 2004, at the Rump Session of CRYPTO 2004, preliminary results were announced by Wang, Feng, Lai, and Yu, nearly an set on on MD5, SHA-0 and other hash functions. The complexity of their attack on SHA-0 is 2forty, significantly meliorate than the attack by Joux et al. [52] [53]

In February 2005, an set on by Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu was appear which could find collisions in SHA-0 in ii39 operations.[four] [54]

Another attack in 2008 applying the boomerang attack brought the complication of finding collisions downward to two33.6, which was estimated to take 1 hour on an average PC from the year 2008.[55]

In low-cal of the results for SHA-0, some experts[ who? ] suggested that plans for the utilize of SHA-one in new cryptosystems should exist reconsidered. After the CRYPTO 2004 results were published, NIST announced that they planned to phase out the employ of SHA-one by 2010 in favor of the SHA-2 variants.[56]

Official validation [edit]

Implementations of all FIPS-canonical security functions tin be officially validated through the CMVP program, jointly run by the National Found of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE). For breezy verification, a bundle to generate a high number of test vectors is fabricated available for download on the NIST site; the resulting verification, still, does not supercede the formal CMVP validation, which is required by police for certain applications.

As of Dec 2013[update], there are over 2000 validated implementations of SHA-1, with fourteen of them capable of treatment messages with a length in $.25 not a multiple of eight (see SHS Validation List Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine).

Examples and pseudocode [edit]

Example hashes [edit]

These are examples of SHA-ane message digests in hexadecimal and in Base64 binary to ASCII text encoding.

-

SHA1("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog")- Outputted hexadecimal:

2fd4e1c67a2d28fced849ee1bb76e7391b93eb12 - Outputted Base64 binary to ASCII text encoding:

L9ThxnotKPzthJ7hu3bnORuT6xI=

- Outputted hexadecimal:

Even a small alter in the message volition, with overwhelming probability, result in many $.25 changing due to the avalanche effect. For example, irresolute dog to cog produces a hash with different values for 81 of the 160 $.25:

-

SHA1("The quick brown play a trick on jumps over the lazy cog")- Outputted hexadecimal:

de9f2c7fd25e1b3afad3e85a0bd17d9b100db4b3 - Outputted Base64 binary to ASCII text encoding:

3p8sf9JeGzr60+haC9F9mxANtLM=

- Outputted hexadecimal:

The hash of the naught-length string is:

-

SHA1("")- Outputted hexadecimal:

da39a3ee5e6b4b0d3255bfef95601890afd80709 - Outputted Base64 binary to ASCII text encoding:

2jmj7l5rSw0yVb/vlWAYkK/YBwk=

- Outputted hexadecimal:

SHA-1 pseudocode [edit]

Pseudocode for the SHA-1 algorithm follows:

Note i: All variables are unsigned 32-flake quantities and wrap modulo 232 when calculating, except for ml, the message length, which is a 64-chip quantity, and hh, the message assimilate, which is a 160-flake quantity. Note ii: All constants in this pseudo code are in big endian. Within each word, the most significant byte is stored in the leftmost byte position Initialize variables: h0 = 0x67452301 h1 = 0xEFCDAB89 h2 = 0x98BADCFE h3 = 0x10325476 h4 = 0xC3D2E1F0 ml = message length in bits (always a multiple of the number of bits in a graphic symbol). Pre-processing: append the chip '1' to the message eastward.thou. past adding 0x80 if message length is a multiple of 8 bits. append 0 ≤ k < 512 bits '0', such that the resulting message length in bits is congruent to −64 ≡ 448 (modernistic 512) append ml, the original message length in bits, equally a 64-bit large-endian integer. Thus, the total length is a multiple of 512 $.25. Process the bulletin in successive 512-bit chunks: break bulletin into 512-bit chunks for each chunk break chunk into sixteen 32-flake big-endian words w[i], 0 ≤ i ≤ xv Message schedule: extend the sixteen 32-scrap words into 80 32-chip words: for i from 16 to 79 Note three: SHA-0 differs by not having this leftrotate. w[i] = (w[i-3] xor westward[i-8] xor w[i-14] xor w[i-16]) leftrotate ane Initialize hash value for this clamper: a = h0 b = h1 c = h2 d = h3 e = h4 Principal loop: [10] [57] for i from 0 to 79 if 0 ≤ i ≤ 19 and then f = (b and c) or ((non b) and d) k = 0x5A827999 else if 20 ≤ i ≤ 39 f = b xor c xor d thousand = 0x6ED9EBA1 else if 40 ≤ i ≤ 59 f = (b and c) or (b and d) or (c and d) grand = 0x8F1BBCDC else if 60 ≤ i ≤ 79 f = b xor c xor d k = 0xCA62C1D6 temp = (a leftrotate v) + f + e + thou + west[i] due east = d d = c c = b leftrotate 30 b = a a = temp Add this chunk's hash to result then far: h0 = h0 + a h1 = h1 + b h2 = h2 + c h3 = h3 + d h4 = h4 + e Produce the final hash value (big-endian) every bit a 160-flake number: hh = (h0 leftshift 128) or (h1 leftshift 96) or (h2 leftshift 64) or (h3 leftshift 32) or h4

The number hh is the message digest, which tin can be written in hexadecimal (base 16).

The called constant values used in the algorithm were causeless to be nothing up my sleeve numbers:

- The four round constants

grandare 230 times the square roots of 2, iii, 5 and 10. Nonetheless they were incorrectly rounded to the nearest integer instead of being rounded to the nearest odd integer, with equilibrated proportions of nil and one bits. As well, choosing the square root of 10 (which is not a prime number) fabricated it a common gene for the two other chosen foursquare roots of primes 2 and v, with perhaps usable arithmetic backdrop across successive rounds, reducing the strength of the algorithm against finding collisions on some bits. - The first four starting values for

h0throughh3are the same with the MD5 algorithm, and the 5th (forh4) is similar. Nevertheless they were not properly verified for being resistant against inversion of the few kickoff rounds to infer possible collisions on some bits, usable by multiblock differential attacks.

Instead of the formulation from the original FIPS PUB 180-1 shown, the following equivalent expressions may be used to compute f in the primary loop above:

Bitwise pick between c and d, controlled past b. (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = d xor (b and (c xor d)) (culling one) (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = (b and c) or ((not b) and d) (alternative 2) (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = (b and c) xor ((non b) and d) (culling 3) (0 ≤ i ≤ nineteen): f = vec_sel(d, c, b) (alternative iv) [premo08] Bitwise bulk office. (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) or (d and (b or c)) (alternative 1) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) or (d and (b xor c)) (alternative 2) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) xor (d and (b xor c)) (culling 3) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) xor (b and d) xor (c and d) (alternative iv) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = vec_sel(c, b, c xor d) (culling v)

It was besides shown[58] that for the rounds 32–79 the computation of:

w[i] = (w[i-iii] xor w[i-viii] xor w[i-14] xor west[i-16]) leftrotate 1

tin exist replaced with:

w[i] = (west[i-6] xor w[i-sixteen] xor westward[i-28] xor w[i-32]) leftrotate ii

This transformation keeps all operands 64-scrap aligned and, by removing the dependency of w[i] on west[i-iii], allows efficient SIMD implementation with a vector length of 4 like x86 SSE instructions.

Comparison of SHA functions [edit]

In the table beneath, internal state means the "internal hash sum" later each compression of a data block.

| Algorithm and variant | Output size (bits) | Internal country size ($.25) | Block size (bits) | Rounds | Operations | Security against collision attacks (bits) | Security against length extension attacks (bits) | Performance on Skylake (median cpb)[59] | First published | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long messages | 8 bytes | ||||||||||

| MD5 (as reference) | 128 | 128 (4 × 32) | 512 | 64 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (modern 232), Or | ≤ 18 (collisions found)[lx] | 0 | 4.99 | 55.00 | 1992 | |

| SHA-0 | 160 | 160 (5 × 32) | 512 | eighty | And, Xor, Rot, Add together (modernistic 232), Or | < 34 (collisions found) | 0 | ≈ SHA-ane | ≈ SHA-1 | 1993 | |

| SHA-1 | < 63 (collisions found)[61] | iii.47 | 52.00 | 1995 | |||||||

| SHA-ii | SHA-224 SHA-256 | 224 256 | 256 (viii × 32) | 512 | 64 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 232), Or, Shr | 112 128 | 32 0 | 7.62 7.63 | 84.l 85.25 | 2004 2001 |

| SHA-384 | 384 | 512 (eight × 64) | 1024 | eighty | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod ii64), Or, Shr | 192 | 128 (≤ 384) | 5.12 | 135.75 | 2001 | |

| SHA-512 | 512 | 512 (8 × 64) | 1024 | 80 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 264), Or, Shr | 256 | 0[62] | 5.06 | 135.fifty | 2001 | |

| SHA-512/224 SHA-512/256 | 224 256 | 512 (viii × 64) | 1024 | 80 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod two64), Or, Shr | 112 128 | 288 256 | ≈ SHA-384 | ≈ SHA-384 | 2012 | |

| SHA-3 | SHA3-224 SHA3-256 SHA3-384 SHA3-512 | 224 256 384 512 | 1600 (five × 5 × 64) | 1152 1088 832 576 | 24 [63] | And, Xor, Rot, Not | 112 128 192 256 | 448 512 768 1024 | 8.12 8.59 11.06 xv.88 | 154.25 155.50 164.00 164.00 | 2015 |

| SHAKE128 SHAKE256 | d (arbitrary) d (arbitrary) | 1344 1088 | min(d/2, 128) min(d/2, 256) | 256 512 | seven.08 viii.59 | 155.25 155.l | |||||

Implementations [edit]

Beneath is a listing of cryptography libraries that back up SHA-1:

- Botan

- Boisterous Castle

- cryptlib

- Crypto++

- Libgcrypt

- Mbed TLS

- Nettle

- LibreSSL

- OpenSSL

- GnuTLS

Hardware acceleration is provided past the post-obit processor extensions:

- Intel SHA extensions: Available on some Intel and AMD x86 processors.

- VIA PadLock

Meet besides [edit]

- Comparison of cryptographic hash functions

- Hash office security summary

- International Association for Cryptologic Research

- Secure Hash Standard

Notes [edit]

- ^ Stevens, Marc (June 19, 2012). Attacks on Hash Functions and Applications (PDF) (Thesis). Leiden University. hdl:1887/19093. ISBN9789461913173. OCLC 795702954.

- ^ a b c Stevens, Marc; Bursztein, Elie; Karpman, Pierre; Albertini, Ange; Markov, Yarik (2017). Katz, Jonathan; Shacham, Hovav (eds.). The First Standoff for Full SHA-ane (PDF). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Scientific discipline. Vol. 10401. Springer. pp. 570–596. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-63688-7_19. ISBN9783319636870. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2017. Lay summary – Google Security Blog (Feb 23, 2017).

- ^ a b "The end of SHA-1 on the Public Web". Mozilla Security Blog . Retrieved 2019-05-29 .

- ^ a b c "SHA-1 Broken – Schneier on Security".

- ^ a b "Critical flaw demonstrated in common digital security algorithm". Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b "New Cryptanalytic Results Against SHA-1 – Schneier on Security".

- ^ a b c Gaëtan Leurent; Thomas Peyrin (2020-01-05). "SHA-1 is a Shambles First Chosen-Prefix Collision on SHA-1 and Application to the PGP Spider web of Trust" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Annal, Report 2020/014.

- ^ a b "Google volition drop SHA-1 encryption from Chrome past January ane, 2017". VentureBeat. 2015-12-18. Retrieved 2019-05-29 .

- ^ a b c d due east Stevens1, Marc; Karpman, Pierre; Peyrin, Thomas. "The SHAppening: freestart collisions for SHA-one". Retrieved 2015-10-09 .

- ^ a b "Archived re-create" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2019-09-23 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Schneier, Bruce (Feb 18, 2005). "Schneier on Security: Cryptanalysis of SHA-1".

- ^ "NIST.gov – Computer Security Sectionalization – Estimator Security Resources Center". Archived from the original on 2011-06-25. Retrieved 2019-01-05 .

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (viii October 2015). "SHA-one Freestart Collision". Schneier on Security.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (2016-05-04). "Microsoft to retire support for SHA1 certificates in the adjacent 4 months". Ars Technica . Retrieved 2019-05-29 .

- ^ "CWI, Google denote first standoff for Industry Security Standard SHA-1". Retrieved 2017-02-23 .

- ^ Barker, Elaine (May 2020). "Recommendation for Key Direction: Office one – General, Table iii". NIST, Technical Written report: 56. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-57pt1r5.

- ^ "RSA FAQ on Capstone".

- ^ Selvarani, R.; Aswatha, Kumar; T 5 Suresh, Kumar (2012). Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Calculating. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 551. ISBN978-81-322-0740-5.

- ^ Secure Hash Standard, Federal Information Processing Standards Publication FIPS PUB 180, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 11 May 1993

- ^ Kramer, Samuel (11 July 1994). "Proposed Revision of Federal Data Processing Standard (FIPS) 180, Secure Hash Standard". Federal Register.

- ^ fgrieu. "Where can I find a clarification of the SHA-0 hash algorithm?". Cryptography Stack Commutation.

- ^ National Establish on Standards and Technology Computer Security Resource Eye, NIST'due south March 2006 Policy on Hash Functions Archived 2014-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 28, 2012.

- ^ National Institute on Standards and Technology Estimator Security Resource Heart, NIST'south Policy on Hash Functions Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 28, 2012.

- ^ "Tech Talk: Linus Torvalds on git". YouTube . Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. "Re: Starting to think about sha-256?". marc.info . Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoyun; Yin, Yiqun Lisa; Yu, Hongbo (2005-08-14). Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-1 (PDF). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2005. Lecture Notes in Information science. Vol. 3621. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 17–36. doi:ten.1007/11535218_2. ISBN978-3-540-28114-half dozen.

- ^ Sotirov, Alexander; Stevens, Marc; Appelbaum, Jacob; Lenstra, Arjen; Molnar, David; Osvik, Dag Arne; de Weger, Benne (December thirty, 2008). "MD5 considered harmful today: Creating a rogue CA certificate". Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Strengths of Keccak – Design and security". The Keccak sponge function family. Keccak team. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

Different SHA-1 and SHA-2, Keccak does not have the length-extension weakness, hence does not demand the HMAC nested construction. Instead, MAC computation can exist performed by simply prepending the message with the key.

- ^ Niels Ferguson, Bruce Schneier, and Tadayoshi Kohno, Cryptography Technology, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN 978-0-470-47424-ii

- ^ Rijmen, Vincent; Oswald, Elisabeth (2005). "Update on SHA-1". Cryptology ePrint Archive.

- ^ Collision Search Attacks on SHA1 Archived 2005-02-19 at the Wayback Car, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ Lemos, Robert. "Fixing a hole in security". ZDNet.

- ^ Cochran, Martin (2007). "Notes on the Wang et al. 263 SHA-1 Differential Path".

- ^ De Cannière, Christophe; Rechberger, Christian (2006-11-15). "Finding SHA-1 Characteristics: General Results and Applications". Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4284. pp. i–20. doi:10.1007/11935230_1. ISBN978-3-540-49475-one.

- ^ "IAIK Krypto Group — Description of SHA-ane Standoff Search Project". Archived from the original on 2013-01-fifteen. Retrieved 2009-06-30 .

- ^ "Collisions for 72-step and 73-step SHA-1: Improvements in the Method of Characteristics". Retrieved 2010-07-24 .

- ^ "SHA-one Collision Search Graz". Archived from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-06-30 .

- ^ "heise online – IT-News, Nachrichten und Hintergründe". heise online.

- ^ "Crypto 2006 Rump Schedule".

- ^ Manuel, Stéphane. "Nomenclature and Generation of Disturbance Vectors for Standoff Attacks against SHA-1" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive . Retrieved 2011-05-nineteen .

- ^ Manuel, Stéphane (2011). "Classification and Generation of Disturbance Vectors for Collision Attacks against SHA-i". Designs, Codes and Cryptography. 59 (i–3): 247–263. doi:x.1007/s10623-010-9458-9. S2CID 47179704. the most efficient disturbance vector is Codeword2 start reported by Jutla and Patthak

- ^ "SHA-one collisions now 2^52" (PDF).

- ^ McDonald, Cameron; Hawkes, Philip; Pieprzyk, Josef (2009). "Differential Path for SHA-ane with complexity O(252)". Cryptology ePrint Annal. (withdrawn)

- ^ "Cryptanalysis of MD5 & SHA-i" (PDF).

- ^ "When Will We See Collisions for SHA-ane? – Schneier on Security".

- ^ "Google Project Hosting".

- ^ Marc Stevens (2012-06-19). "Attacks on Hash Functions and Applications" (PDF). PhD Thesis.

- ^ Leurent, Gaëtan; Peyrin, Thomas (2019). "From Collisions to Called-Prefix Collisions Application to Full SHA-1" (PDF). Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2019. Lecture Notes in Information science. Vol. 11478. pp. 527–555. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17659-4_18. ISBN978-3-030-17658-seven. S2CID 153311244.

- ^ Gaëtan Leurent; Thomas Peyrin (2019-04-24). "From Collisions to Chosen-Prefix Collisions - Awarding to Full SHA-ane" (PDF). Eurocrypt 2019.

- ^ Chabaud, Florent; Joux, Antoine (1998). Krawczyk, Hugo (ed.). Differential collisions in SHA-0 (PDF). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 1998. Lecture Notes in Figurer Science. Vol. 1462. Springer. pp. 56–71. CiteSeerX10.1.1.138.5141. doi:10.1007/bfb0055720. ISBN9783540648925.

- ^ Biham, Eli; Chen, Rafi. "Near-Collisions of SHA-0" (PDF).

- ^ "Report from Crypto 2004". Archived from the original on 2004-08-21. Retrieved 2004-08-23 .

- ^ Grieu, Francois (18 August 2004). "Re: Any advance news from the crypto rump session?". Newsgroup: sci.crypt. Event occurs at 05:06:02 +0200. Usenet: fgrieu-05A994.05060218082004@individual.net.

- ^ Efficient Collision Search Attacks on SHA-0 Archived 2005-09-10 at the Wayback Machine, Shandong University

- ^ Manuel, Stéphane; Peyrin, Thomas (2008-02-eleven). Collisions on SHA-0 in I Hour (PDF). Fast Software Encryption 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5086. pp. 16–35. doi:ten.1007/978-3-540-71039-4_2. ISBN978-3-540-71038-seven.

- ^ "NIST Brief Comments on Contempo Cryptanalytic Attacks on Secure Hashing Functions and the Continued Security Provided by SHA-ane" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-05-05 .

- ^ "RFC 3174 – US Secure Hash Algorithm 1 (SHA1)".

- ^ Locktyukhin, Max; Farrel, Kathy (2010-03-31), "Improving the Operation of the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-1)", Intel Software Knowledge Base of operations , retrieved 2010-04-02

- ^ "Measurements table". demote.cr.yp.to.

- ^ Tao, Xie; Liu, Fanbao; Feng, Dengguo (2013). Fast Standoff Assail on MD5 (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive (Technical report). IACR.

- ^ Stevens, Marc; Bursztein, Elie; Karpman, Pierre; Albertini, Ange; Markov, Yarik. The first standoff for full SHA-1 (PDF) (Technical study). Google Inquiry. Lay summary – Google Security Blog (Feb 23, 2017).

- ^ Without truncation, the total internal state of the hash function is known, regardless of collision resistance. If the output is truncated, the removed part of the state must be searched for and found earlier the hash function can be resumed, allowing the attack to proceed.

- ^ "The Keccak sponge role family". Retrieved 2016-01-27 .

References [edit]

- Eli Biham, Rafi Chen, Near-Collisions of SHA-0, Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2004/146, 2004 (appeared on CRYPTO 2004), IACR.org

- Xiaoyun Wang, Hongbo Yu and Yiqun Lisa Yin, Efficient Collision Search Attacks on SHA-0, Crypto 2005

- Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin and Hongbo Yu, Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-i, Crypto 2005

- Henri Gilbert, Helena Handschuh: Security Assay of SHA-256 and Sisters. Selected Areas in Cryptography 2003: pp175–193

- An Illustrated Guide to Cryptographic Hashes

- "Proposed Revision of Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 180, Secure Hash Standard". Federal Annals. 59 (131): 35317–35318. 1994-07-11. Retrieved 2007-04-26 . [ permanent expressionless link ]

- A. Cilardo, Fifty. Esposito, A. Veniero, A. Mazzeo, 5. Beltran, East. Ayugadé, A CellBE-based HPC application for the analysis of vulnerabilities in cryptographic hash functions, High Operation Calculating and Communication international conference, August 2010

External links [edit]

- CSRC Cryptographic Toolkit – Official NIST site for the Secure Hash Standard

- FIPS 180-4: Secure Hash Standard (SHS)

- RFC 3174 (with sample C implementation)

- Interview with Yiqun Lisa Yin concerning the attack on SHA-one

- Explanation of the successful attacks on SHA-1 (3 pages, 2006)

- Cryptography Research – Hash Standoff Q&A

- SHA-ane at Curlie

- Lecture on SHA-i (1h 18m) on YouTube by Christof Paar

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-1

0 Response to "Sha Is Perhaps the Most Widely Used Family of Hash Functions."

Post a Comment